Sometimes, the best candidates aren’t actually the best candidates.

We have a tendency to prefer candidates who are more outgoing, conversational, and energetic — especially for customer-facing frontline roles. These individuals often come across as confident and socially adept, and research consistently shows that extraverted individuals tend to perform well in interviews. They’re quick on their feet, passionate, and generally likable. Naturally, hiring managers and recruiters will gravitate to these types of candidates.

This is perfectly normal human behavior. But it also might just be the cause for the high short-term turnover you’re experiencing. It’s called extraversion bias — and it’s something incredibly easy to fall prey to, precisely because it often feels so right. Despite your best efforts and diligence in the screening and assessment process, selecting the most passionate, extraverted candidates (the ones who seem like no-brainers) can actually lead you to mismatched hires. Bad hires occur more often than we might think and they have hidden costs from lost time and money to potentially damaging the reputation of your organization. Extraversion bias is a major contributing factor to making bad hires.

The truth is that while extraversion can certainly be an asset, it’s not a universal indicator of job success. In fact, for some roles, high levels of extraversion can actually be incompatible.

Let’s take a frontline cashier role as an example. Sure, an extraverted candidate might seem perfect on paper — they’re engaging, upbeat, and great with people. But people with high levels of extraversion also tend to be more sensation-seeking, increasing the likelihood they’ll get bored and start looking for their next opportunity if the role isn’t particularly interesting to them.

On the other side, consider roles that require more focus and less interaction, like working behind the scenes in a kitchen or managing inventory in a stockroom. A highly extraverted candidate might ace the interview, but once in the role, they may feel under-stimulated and disengaged, increasing the risk of early turnover.

Candidates that are more introverted might not be as flashy in an interview or come across as super passionate. Introverts tend to speak less frequently or seem more reserved. But those qualities often come with strengths that are undervalued: deep listening, thoughtfulness, and consistency. In fact, introverted employees are often better listeners — an essential skill in roles that require attention, following processes, or dealing with sensitive customer issues. When they do speak, it’s often with care and insight, qualities that contribute to stronger team dynamics and problem-solving over time.

What this all boils down to is fit — not personality in isolation, but how a candidate’s natural tendencies align with the demands of a particular role. In most cases, the ideal outcome is a candidate who doesn’t exist on the extreme ends of extraversion or introversion, but has the ideal blend of traits to succeed in a role long term.

I know how hard it can be to break free from our intuition. The interview process is basically designed for extraverts to thrive, and it’s not reasonable to expect time-strapped managers to have the capacity to dig deeper. If they interview a qualified, amicable candidate that they have an immediate connection with, they’re not going to hesitate to extend an offer.

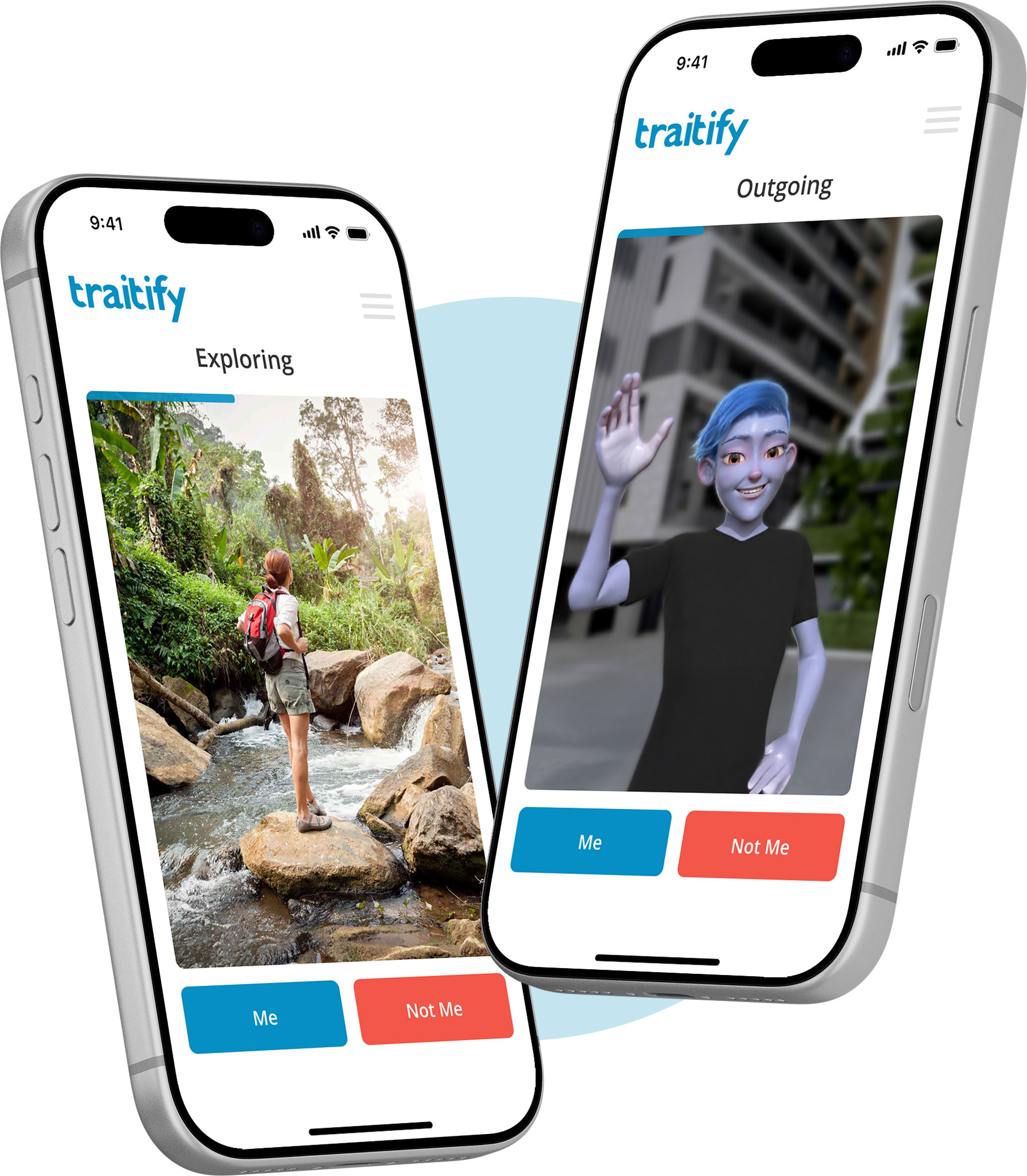

Assessments remove some of the mental burden on managers and provide them with a deeper layer of information they can use to determine who is actually a match for a role. Rather than overvaluing the most personable candidate, we help hiring teams see the fuller picture. For example, if you’re hiring for a role where reliability, attention to detail, and task focus are key, our assessment will help you identify candidates who might not dazzle in a traditional interview, but are a better long-term match.

Again, I’m not saying extraverts are always bad hires. Far from it. The best way to approach this is on a spectrum. For many frontline roles, certain traits that extraverts possess are going to be valuable, if not essential — but does that role require the most extraversion? Probably not. Part of the problem is that we assume that extraverted individuals are more passionate about their work. In reality, they just express their passion differently from introverted individuals. Extraverts are more likely to express their passion vocally and with great enthusiasm, while introverts are more likely to express passion through hard work and a focus on quality which are less visible. Moving past a one-size-fits-all mindset and embracing a more nuanced approach to talent selection will open your candidate pool in ways that will start to solve certain frontline challenges like short-term turnover.

Extraversion bias has been known for a long time in the scientific community, but it still feels like a fairly unexplored topic in the world of talent — one that can unknowingly skew your hiring decisions, especially when speed is of the essence. But with the right tools, science, and a little reflection, you can avoid falling into the trap of hiring the flashiest candidates on the surface, and find more of the right people for your role who will still be making a positive impact months from now.

Because at the end of the day, frontline hiring shouldn’t just be fast. It should be smart.